Let’s get back to some Technique Tuesday posts! This week, we’ve decided to tackle movement. Though this isn’t really a “technique,” it’s an aspect of art that many artists incorporate into their works and we thought we should talk a little about it!

What is it?

Movement is the way in which a piece can express a fluid motion or the possibility of it. It can be achieved in many ways, from the portrayal of a subject performing an activity to the distortion of the atmosphere within a scene. I would say that it’s easier to demonstrate action within figurative works in comparison to still lifes and landscapes, though these genres certainly can contain movement.

Depth, perspective, and painted strokes all have influence on whether a piece has movement, too. For example, the amalgamation of stroke marks aimed in a similar direction can express movement. The other two spatial factors, depth and perspective, are the means through which movement is possible. Space allows for dynamism and maneuverability of the subject, hence its affect upon a piece’s movement. What’s interesting is that it could also be stated in the reverse – that movement alludes to spatial depth.

Examples in art history:

Though movement can be traced throughout all of art history, I would just like to point out notable works that have this technique. As stated earlier, painted strokes, like those presented in Vincent van Gogh’s “Starry Night,” can create the allusion of motion. Here, the grouping of multiple painted strokes in a similar direction illustrates the movement of the wind, clouds, and night sky.

Vincent van Gogh, “Starry Night,” 1889

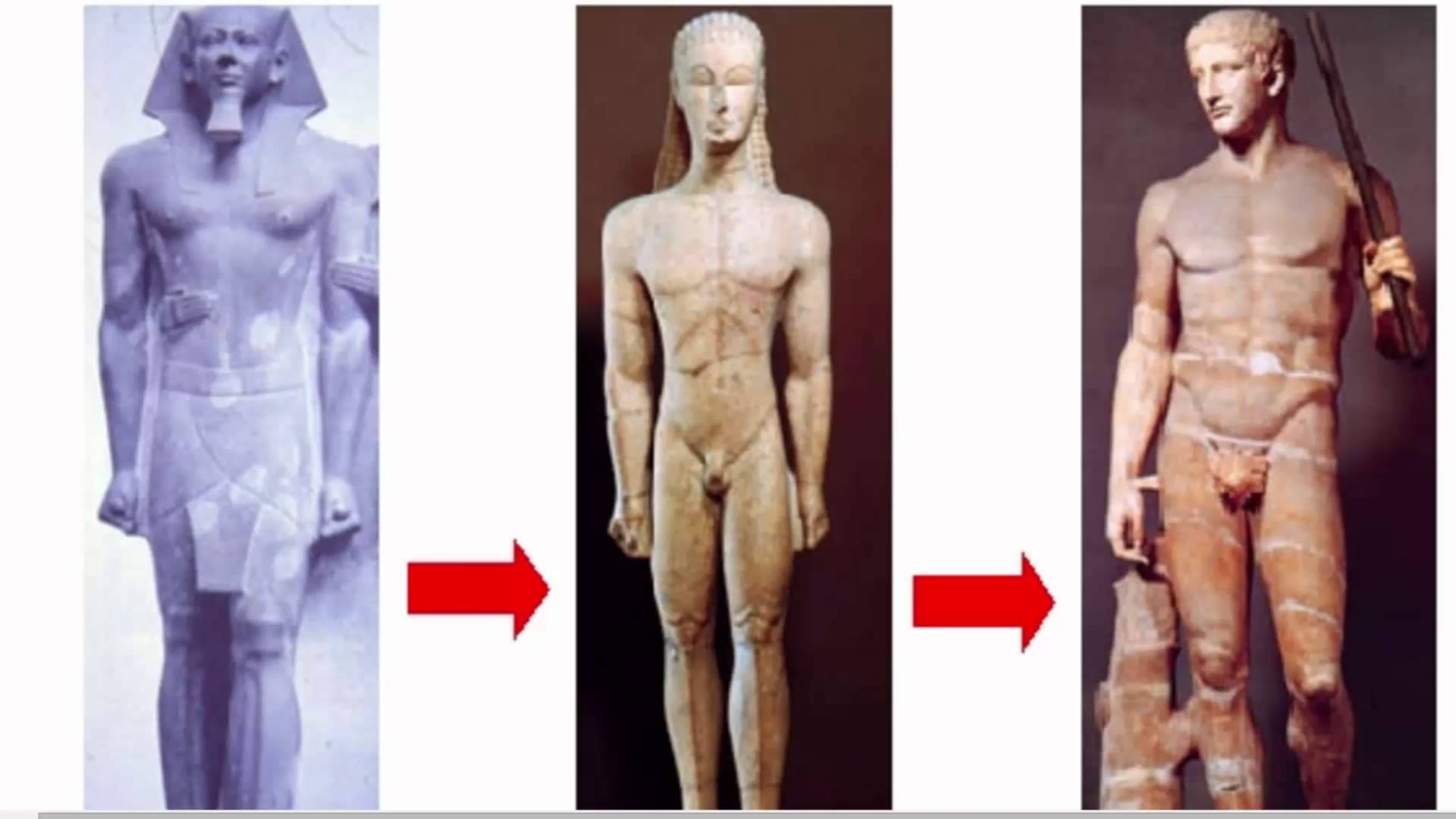

Another aspect that can allude to movement, specifically in figurative works, is the positioning of the human body. In ancient Greek, the concept of readjusting the body from a flat, stagnant position to a more dynamic posture became known as contrapposto. It is particularly defined as a relaxed stance where the body’s weight is shifted to one side, causing the shoulders and hips to drop on alternating sides. Not only did this make the work more realistic, but it added liveliness and dimension – key aspects of movement. Displayed below is the artistic development of contrapposto as demonstrated through sculpture, beginning with the ancient Egyptian “King Menkaure and his Queen,” then the archaic Greek “Kritios Boy,” and ending with a classical Greek athlete.

Each sculpture is significant in art history for they represent a culture’s perspective of ideals through contemporary craftsmanship. The progression seen above also presents a culture’s understanding of anatomical mobility and how to express it through rigid materials, like stone and marble. From the illustration above, it is evident that figurative movement was not only an artistic technique that improved through time, but that figurative movement was specifically achieved through the forward placement of the subject’s foot to a more realistic posture of contrapposto.

Marcel Duchamp, “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2,” 1912

Jumping thousands of years ahead, movement later became a technique that was constantly manipulated from realism into abstraction. Modern artists, especially within the early 20th century, had analyzed ways in which to distort forms and generate them into familiar, abstract compositions – think along the lines of Picasso and cubism! One such example of this technique’s tranformation into abstraction is seen in Marcel Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.” Here, Duchamp used overlapping shapes and swift, downward strokes to notion the idea of a nude descending a staircase. The overlapping shapes also help define the figure’s movement and the pictorial depth – the space is not flat and two-dimensional, though the figure may seem to lay flat. If you look closely, the nude also seems to sashay down due to the different shapes’ placements, alluding to the classic contrapposto position and thus movement. I would also like to note that this piece visually relates to a series in that it uses the concept of time as well as multiple frames or individualized steps to express a subject’s progression. All of these factors, the overlapping shapes to the figure’s posture, demonstrate movement.

Another great modern art example is Umberto Boccioni’s “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space.” Compared to the classical sculptures above, the artist integrated abstract concepts of movement similar to that seen in Duchamp’s work. The continuous, smooth planes of the figure’s arms and legs give the allusion that the subject is swiftly running through space. Like Duchamp’s piece, you can visualize the separate, individual motions though they are combined in one gesture. Moreover, the bronze material provides this fluidity of motion where the classical sculptures’ materials could not.

Umberto Boccioni, “Unique Forms of Continuity in Space,” 1913

Examples at Principle Gallery:

Again, many works displayed within the gallery employ this technique, but there are a few that I would like to specifically point out due to their relevance to the topics discussed earlier. Greatly inspired by classicism, it is only fitting to mention Robert Liberace in this post. He consistently creates figurative works that display a subject in motion or who appear to be in motion. Some notable paintings are “Study in Motion,” his “Metamorphosis” series, as well as “Ferryman.” Liberace is successful in portraying movement by using techniques reminiscent of classical works, such as contrapposto as well as pentimenti (traces of the original stroke marks). More specifically, pentimenti is the means through which the artist displays the figure’s previous motions.

Come see Robert Liberace’s mastery of the classics and this technique at his upcoming solo exhibition and painting demonstration on August 18th! Make sure to also check out our website for new arrivals, other events, and all of our available inventory. Feel free to contact us with any questions!